https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/our-solar-system-is-even-stranger-than-we-thought/

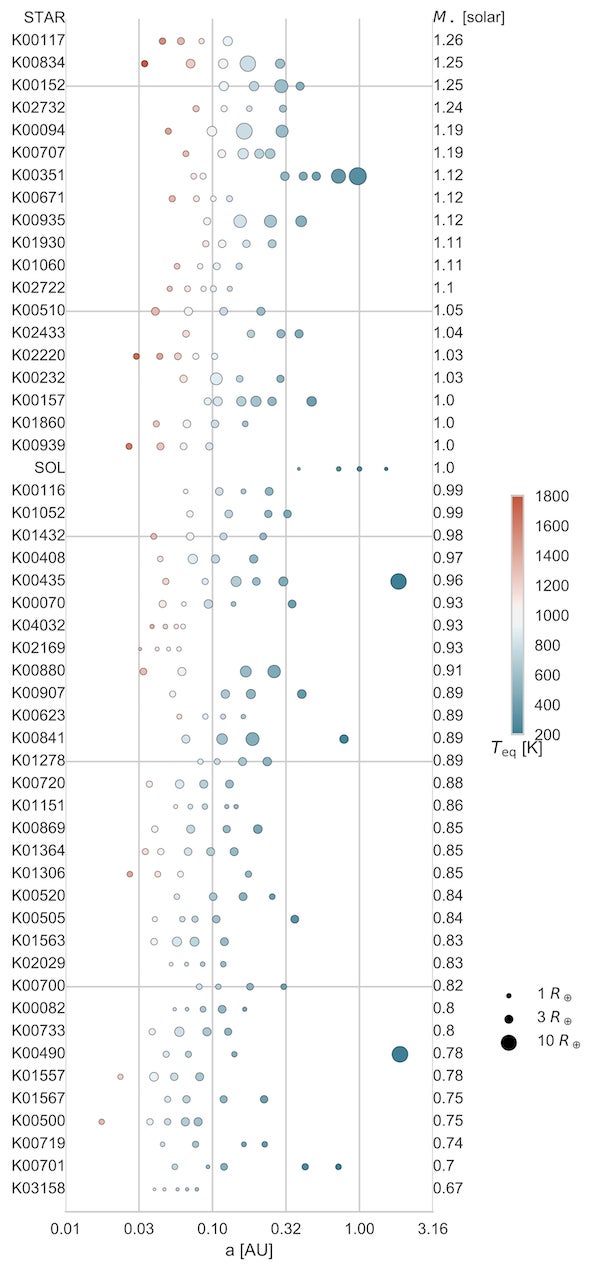

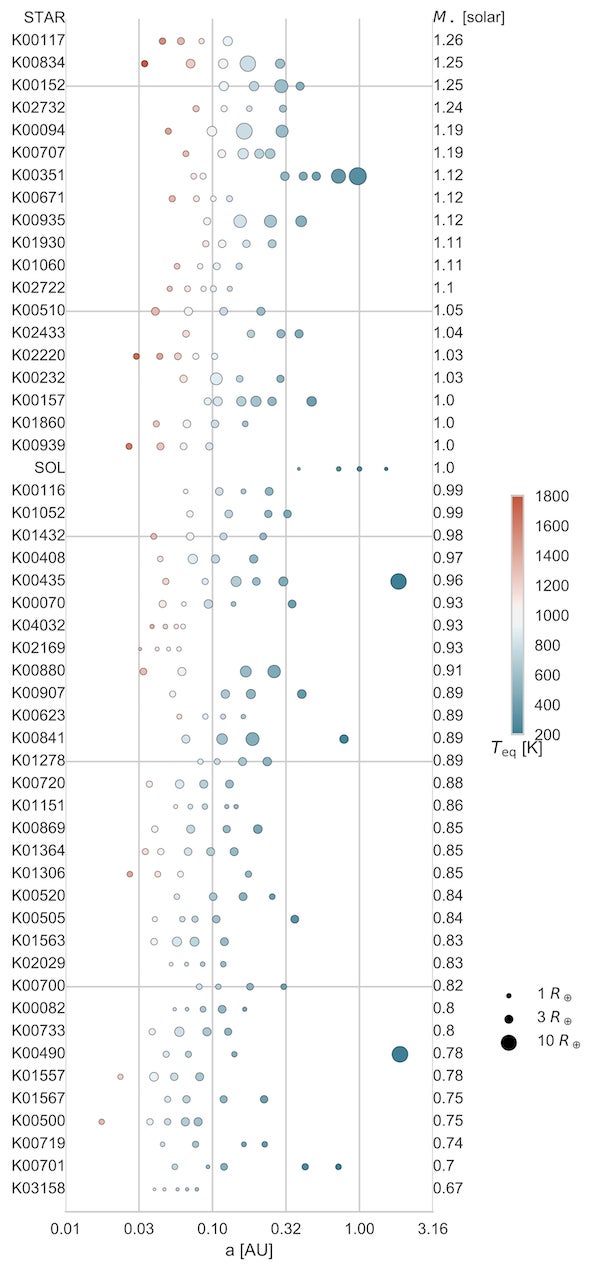

"New research shows a pattern of exoplanet sizes and spacing around other stars unlike what we see in our own system

How special is the solar system? The history of astronomy has mostly been a one-way journey from a worldview in which our solar system is orderly (and divine) to a view in which we are not special. Our solar system’s planets, once thought to dance in god-ordained perfect circles in a “music of the spheres,” deviate from circular orbits. Johannes Kepler, who demonstrated the non-circular orbits of the planets, tried to restore a sense of heavenliness by latching onto a new pattern for their orbits based on Plato’s mathematical solids—but that notion was discredited many years later with the discovery of Uranus.

So when, on a sunny afternoon in California last year, I discovered a set of patterns that seem to rule planetary systems other than our own, I was skeptical. Were these patterns real, or were they an illusion? And if real, what did they mean about our solar system’s place in the cosmos?"

Has David Braben read this? Can he make some adjustments to the stellar forge and recreate some unexplored systems to new rules?

"New research shows a pattern of exoplanet sizes and spacing around other stars unlike what we see in our own system

How special is the solar system? The history of astronomy has mostly been a one-way journey from a worldview in which our solar system is orderly (and divine) to a view in which we are not special. Our solar system’s planets, once thought to dance in god-ordained perfect circles in a “music of the spheres,” deviate from circular orbits. Johannes Kepler, who demonstrated the non-circular orbits of the planets, tried to restore a sense of heavenliness by latching onto a new pattern for their orbits based on Plato’s mathematical solids—but that notion was discredited many years later with the discovery of Uranus.

So when, on a sunny afternoon in California last year, I discovered a set of patterns that seem to rule planetary systems other than our own, I was skeptical. Were these patterns real, or were they an illusion? And if real, what did they mean about our solar system’s place in the cosmos?"

Has David Braben read this? Can he make some adjustments to the stellar forge and recreate some unexplored systems to new rules?