In the interview he questions red shift and quite effectively demonstrated why it wasn't a good measurement of distance.

It's not!! It's a good measurement of

relative velocity. Multiply that by time and you get distance.

Seriously, unless you mis-reported it, that's such a horrendous mistake that anyone should have fallen over laughing at it.

Dogma has that way of making people like that.

It's not "dogma" which is theory based on faith or authority (literally, from the Greek: that which seems to be an opinion/belief) - it's theory based on non-contradicting evidence.

For someone to overturn the big bang all they have to do is

present a theory that is not contradicted by any of the observable evidence, or to identify a flaw in the big bang theory that

is supported by observable evidence. The problem with doing that is that there's a preponderance of evidence for the big bang-- including evidence confirming the theory with predictive power -- and other theories are not as well supported by or conforming with observation.

Predictive power is one of the key things that helps bolster a theory. If a theory says, "according to this theory, if we're ever able to observe X, we should observe it consistent with Y and Z ... " and it later does: that shows that extrapolations based on the theory also align with the theory. That's not complete confirmation but it's pretty much over and done once a theory starts having predictive power. For example, the big bang predicts that the universe was once very small and very hot; the only form matter would exist in would be a plasma, until the universe expanded to a certain point and it cooled enough to coalesce into normal state. Plasma is interesting because it's opaque to certain kinds of radiation; the big bang theory therefore predicts that there would be a sort of wall, far enough out, past which it would be impossible to make observations. And, guess what? Turns out that when our technology got good enough we discover that there's a barrier we can't see past - that's an observation that's completely aligned with predictions arising from big bang theory.

More to the point, someone trying to say the big bang didn't happen, such as a steady-stater (hint: there are no steady-staters any more, they're like people who believe the Earth is flat) would have to have a theory that encompassed and explained the cosmic microwave background radiation, also.

I was at a dinner party once and was talking to some quack who had bought the whole "electron universe" malarkey, and basically was saying a whole bunch of stuff was wrong. So I asked him how electron universe explains observations that were in line with general relativity but which weren't predicted by his theory; such as gravitic lensing. *crickets*

Science cuts both ways: if you want to overthrow an established theory you need to find evidence that contradicts that theory, and then - ideally - offer a new theory that

encompasses all the existing observations plus the contradicting observation. This is why you'll note that the great theories usually supplement and build atop earlier theories that had supporting evidence. For example, the universe is, for most purposes, Newtonian. Newton was right about practically everything except when things get small or very fast or huge, and what happens then. Einstein came along and supplemented Newton with a better understanding that beautifully encompassed Newton (because Newton was based on observable reality with the tools that were available at his time) and added a bunch of stuff that never occurred to Newton. So then you had scientists look at Einstein and predict from his theory that you could have, I dunno, gravity so strong it would bend light 100% into its gravity well - it would look like a "black hole" in space. And lo and behold years later, people observe black holes. Black holes aren't just random cool stuff; they are independent validation of one aspect of Einstein's general relativity.

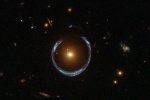

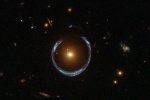

Einstein rather casually predicted a phenomenon called "gravitic lensing" in which a huge mass might bend light the same way a piece of glass does. And then he said "We'll probably never have instruments precise enough to detect it..." He said that in ... 1939 or something like that. And then, now, the Hubble space telescope brings back pictures:

That's a hubble shot of a galaxy behind another galaxy. The blue ring is

the light of the rearmost galaxy, being bent around the nearer galaxy, in accordance with Einstein's theories. What's really bad-azz is that you can use the deflection of light to back-calculate the mass and "weigh" the nearer galaxy.

Einstein FTW.

By now there are so many validations of Einstein that nobody with any education about physics thinks Einstein is wrong but everyone who understands science will say "... of course it's not complete" Someone can come along with some new observations that supplement Einstein. Which is exactly what happened: Quantum mechanics does not contradict relativity; it builds on it and it also fulfils some of its predictions. So, that's beautiful.

The funny bit a lot of people don't seem to want to understand is if you want to try to dismiss something built on QM, you wind up dismissing (potentially) bits of relativity, and (potentially) bits of Newton. And when you run into someone saying that kind of crap, they're talking out their hat.

Edit: QM makes accurate predictions of behaviors of subatomic particles and so far none of those predictions has been wrong. That's pretty good. Quantum Electrodynamics explains everything from how our eyes see color to how our computers work. (Similarly: every GPS, including the one in your cell phone, is proof that Einstein's relativity was right enough to locate you to within a foot on the surface of the planet using the difference in transmission times between geosynchronous satellites in a gravitation field) When some bonehead says QM is wrong, they are saying to discard a theory that has been right about more things than most people can count. You gotta have some nobel prize-winning evidence to make a dent in a theory like that! It is hoped that someday there will be a version of QED that goes farther than current QED and deals with behaviors of and inside nuclei. Feynman and some really smart people busted their brains trying to figure that out. Maybe someone will, someday. But the odds that if someone comes up with a Quantum Nucleodynamics, it will build atop QED and won't disprove it.